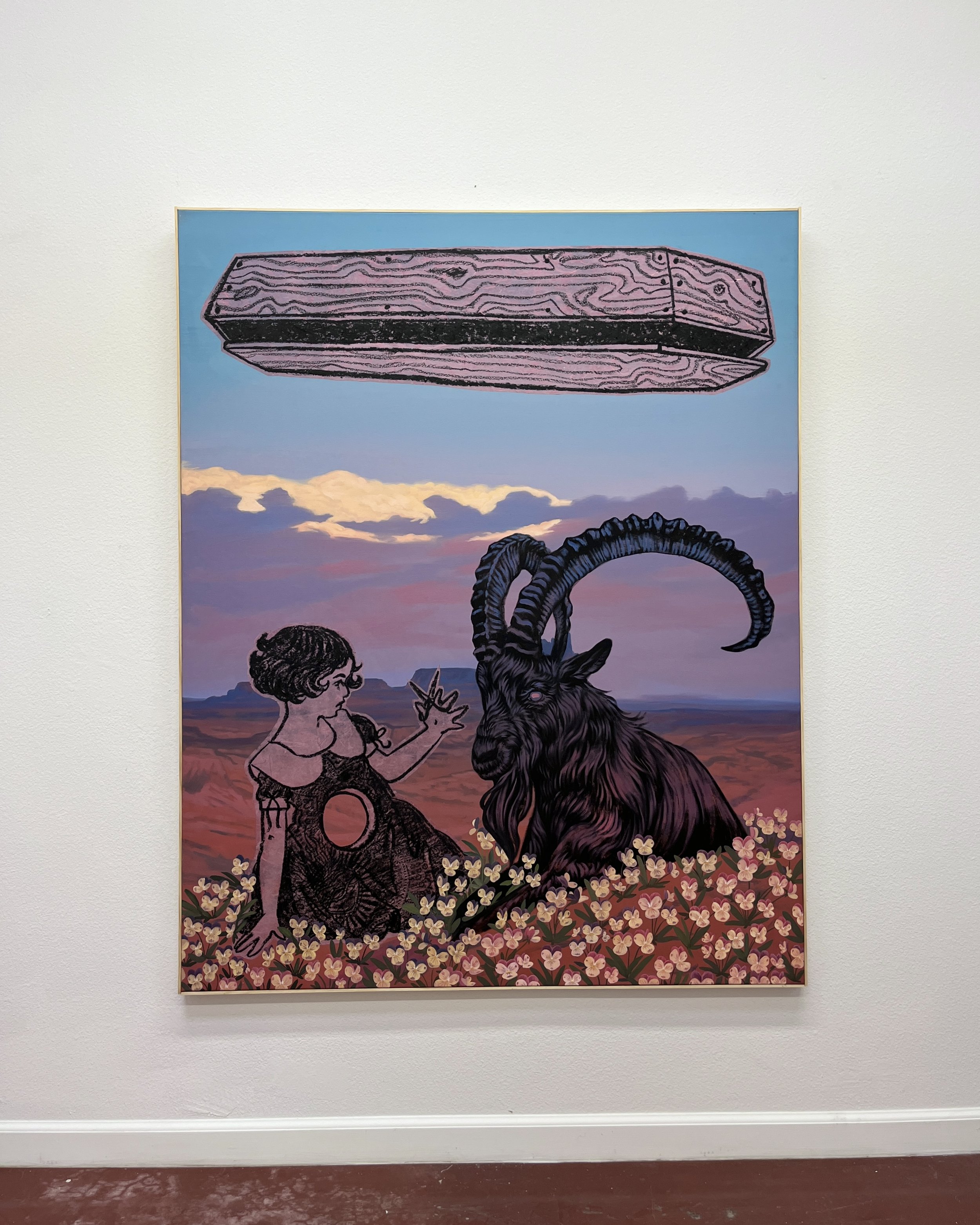

Grief for the Dispossessed, Oil on canvas with mixed media, 60”x 48”, 2024

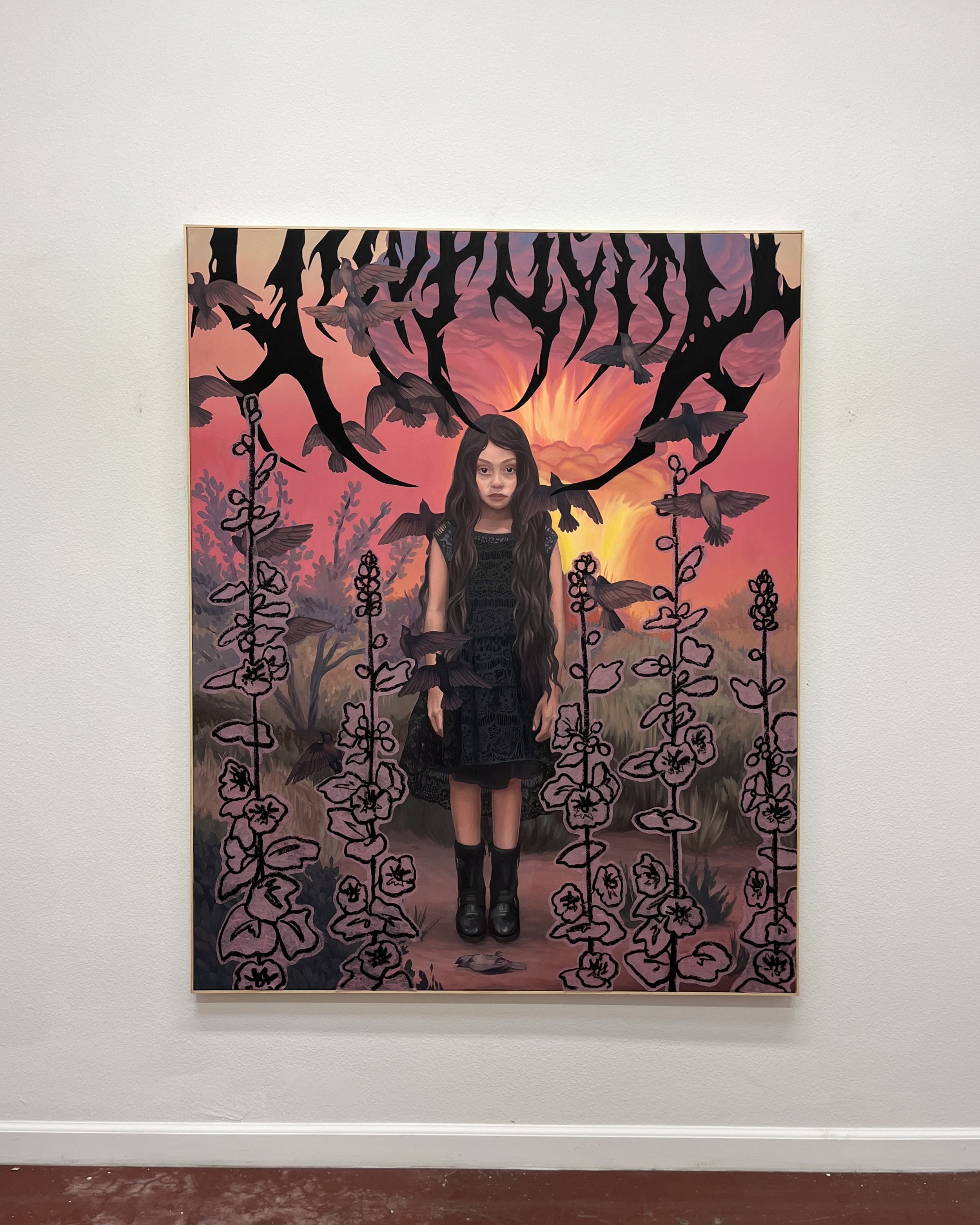

Fears Rooted in Heritage, Oil on canvas with mixed media, 60”x 48”, 2024

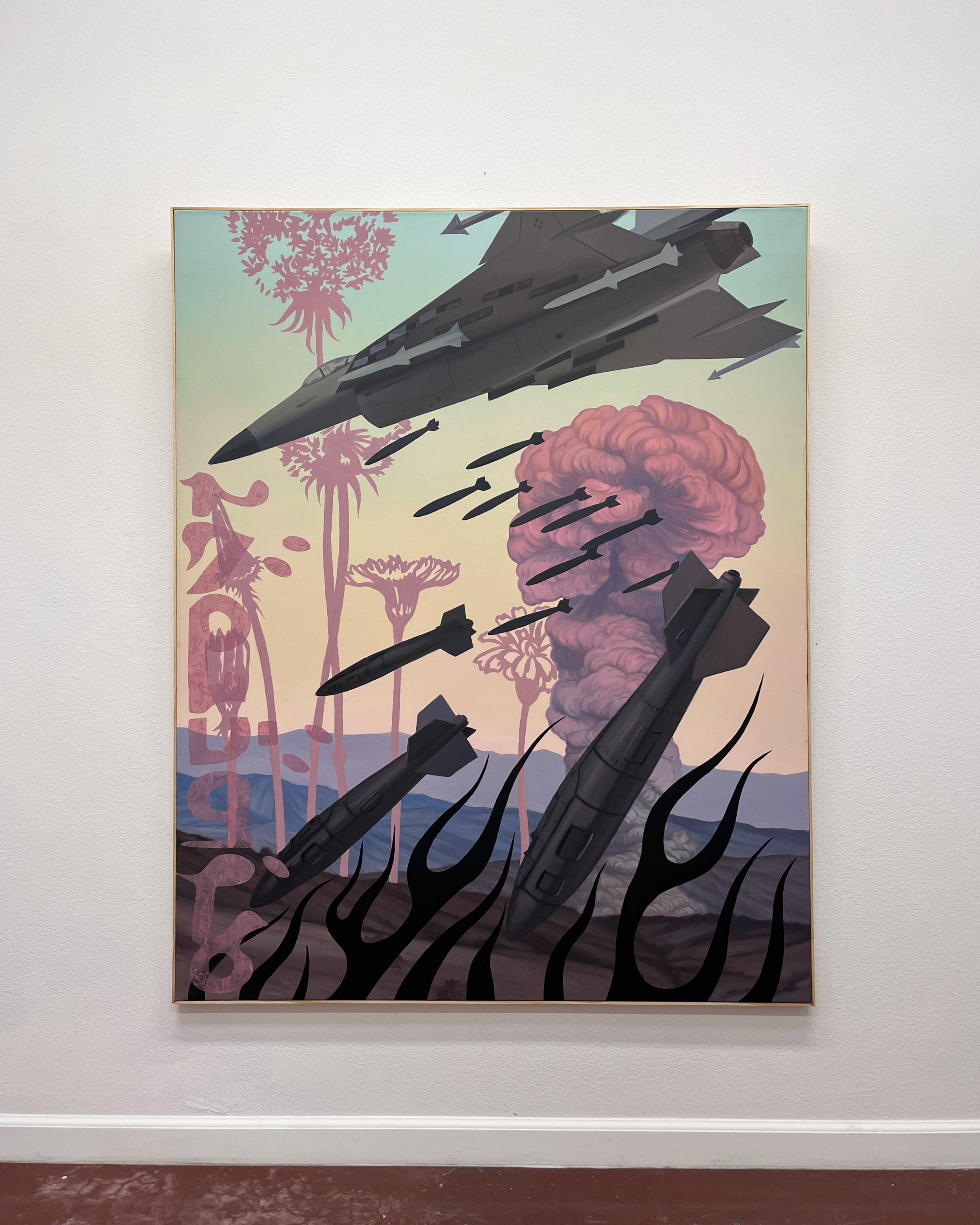

Black Gold, Red Conflict, Oil on canvas with mixed media, 60”x 48”, 2024

War on Agriculture, Oil on canvas with mixed media, 60”x 48”, 2024

Duality of War, Oil on canvas with mixed media, 60”x 48”, 2024

Free Palestine, Oil on canvas with mixed media, 60”x 48”, 2024

Unmoored, Oil on canvas with mixed media, 60”x 48”, 2024

Why Run?, Oil on canvas with mixed media, 60”x 48”, 2024

IVF Battle Ground, Oil on canvas with mixed media, 60”x48”, 2024

Burn the Witch, Oil on canvas with mixed media, 60”x 48”, 2024

Visions of Devastation, Oil on canvas with mixed media, 60”x 48”, 2024

The Verdict of Oppression, Oil on canvas with mixed media, 60”x 48”, 2024

Torn Land, Lifeless Remains, Oil on canvas with mixed media, 60”x 48”, 2024

Bitter Divide, Empty Promises, Oil on canvas with mixed media, 60”x 48”, 2024

ABSTRACT

Mourning is a series of mixed-media works, each measuring 60” x 48” on stretched canvas, confronting two of my deepest fears: war and the erosion of women’s rights. Developed through a systematic, assembly-line process, these pieces layer visual elements to construct a narrative. The backgrounds; landscapes, gradients, and western silhouettes, serve as stages where these narratives unfold, grounding the work in both personal and collective history.

I fear death. I mourn for the future version of myself that will inevitably die. How painful will it be? How will my loved ones receive the news? I have so much left to do, a life I want to live for a long time. And yet, at any moment, through no fault of my own, I could be gone.

In my art, I express these anxieties through the lens of my human condition, shaped by a feminist and feminine perspective. There are four main themes: women’s rights, war, mass killings, and environmental destruction. While I explore the theme of devastation, my work also evokes the presence of the Grim Reaper, an embodiment of fear, sadness, and isolation, while representing women in these contexts. Mourning is both a reckoning with fear and a call for liberation from it, though I remain acutely aware of its inescapable presence.

My work on women’s rights directly responds to the ongoing battle for bodily autonomy, a fundamental human right under attack in my own country. While these policies target women, they ultimately threaten the autonomy of people of all genders. Using sources like Planned Parenthood and firsthand stories from women and girls, I connect viewers to the reality of gender inequality.

My reflections on war are more fragmented. My understanding comes from family stories and limited research, particularly regarding the Assyrian woman’s experience, a narrative rarely published. These fragments of history and personal accounts are woven together, creating a reconstructed narrative that speaks to the complexity of war’s impact on us

As 2024 came to a close, the weight of war and the fight for reproductive rights consumed my thoughts. With this series, I aim to confront viewers with imagery that resonates universally, exposing these fears and realities to encourage reflection, dialogue, and a deeper understanding of our shared vulnerabilities.

The Verdict of Oppression, oil on canvas with mixed media, 60”x 48”, 2024

In The Verdict of Oppression, I use symbols and figures to describe the following: During Donald Trump's 2016 presidential campaign, Trump made it clear that he would appoint pro-life justices to the Supreme Court who would overturn Roe v. Wade. His campaign promise was to win support from conservative and evangelical voters, who prioritize restricting abortion access. I was 16 years old and thought there was no way he could become our president because I believed we/the nation could not go so far backward from the gains women's rights have won over the last fifty years. I was wrong; he became president, and during his presidency, he nominated three conservative justices: Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett. On top of that, Amy Coney Barrett replaced Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a liberal icon and firm defender of abortion rights. Barrett, with known conservative views on abortion, solidified a conservative majority that was instrumental in the Dobbs ruling. Trump’s three appointments created a 6-3 conservative supermajority on the Supreme Court. This shift in the Court’s balance provided the numbers needed to reverse Roe v. Wade. Trump’s influence on the Court has had lasting effects, not only on abortion rights but also on a range of other Issues. By appointing justices with a conservative, originalist philosophy, Trump reshaped the Court in a way that has altered U.S. law for years, possibly decades, and does not represent Americans as a whole.

This piece reflects the outcomes of the 2016 Trump presidency and warns us of his grim reaper-like qualities. The three Supreme Court justices he appointed are represented by the three vultures in the branches, watching the subjects in the foreground. The three mourning girls in the foreground represent the women of America. I used mourning veils for rubbings with the paper to create their lace dresses to dress them for the funeral. In Assyrian Christian culture, mourning veils are used during funeral services to cover the hair of women as a sign of respect for god. The claw coming down is the Grim Reaper; in this case, it’s Trump.

Black Gold, Red Conflict, oil on canvas with mixed media, 60”x48”, 2024

Black Gold, Red Conflict is a piece about the reality of the Iran/Iraq war and how the U.S. played its part. As a country, we preach peace but make decisions based on power. This is one of 14 works I created to critique our history and discuss my fears of ending up at death's door. The U.S. played a painful and contradictory role in the Iran-Iraq War, trying to keep either side from becoming too powerful, especially in the oil-rich region. The U.S. gave intelligence, financial support, and military aid to Iraq. Then, they secretly sold arms to Iran in what became known as the Iran-Contra affair. This “double-dealing” made the conflict last longer, increased suffering, and led to ongoing bitterness in both countries, fueling endless instability in the region. The assault weapons are as much of a grim reaper as the goats. But also, the assault weapons face the live figures, and the oil rig looms over their heads to show death is looming over them.

The Iran/Iraq conflict is just one war my mom and her family lived through to give her this trauma and fear. She lived in fear for the majority of her life, yet my father and brother, the two men in the house, constantly discouraged her from talking about war because she was a woman. They would insensitively speak about people dying in battle and state that it was necessary for the greater good. She and I were automatically considered less knowledgeable about the subject because we were women. We also preferred peaceful politics over violent politics. Growing up, I always attempted to enter these conversations, which usually involved my mom and dad fighting and me trying to de-escalate the situations. I always leaned towards my mom's side because she always advocated for peace and would bring up her fears and real-life stories. She was credible, unlike my father, who had not lived through war himself and had not dealt with the same hardships as her. My father and brother would fight us, saying we didn’t know what we discussed. This is reflected in the story of my dad's planes and how I got ownership of them.

The U.S. intervenes in other countries, stating it’s for humanitarian reasons (like fighting oppressive regimes or aiding civilians during wars). Still, when those displaced by these interventions seek refuge in the U.S., they are met with resistance, restrictive immigration policies, and racism. This contradiction criticizes deeper issues about how the U.S. lacks responsibility for the people impacted by its actions abroad.

From a feminist perspective, the situation is even worse for women and children, who face risks of violence and exploitation in both conflict zones and as refugees. Sometimes, the U.S. uses women’s rights as a justification for intervention. Still, this stance is rarely matched by policies prioritizing their safety and well-being during the conflict or resettlement.